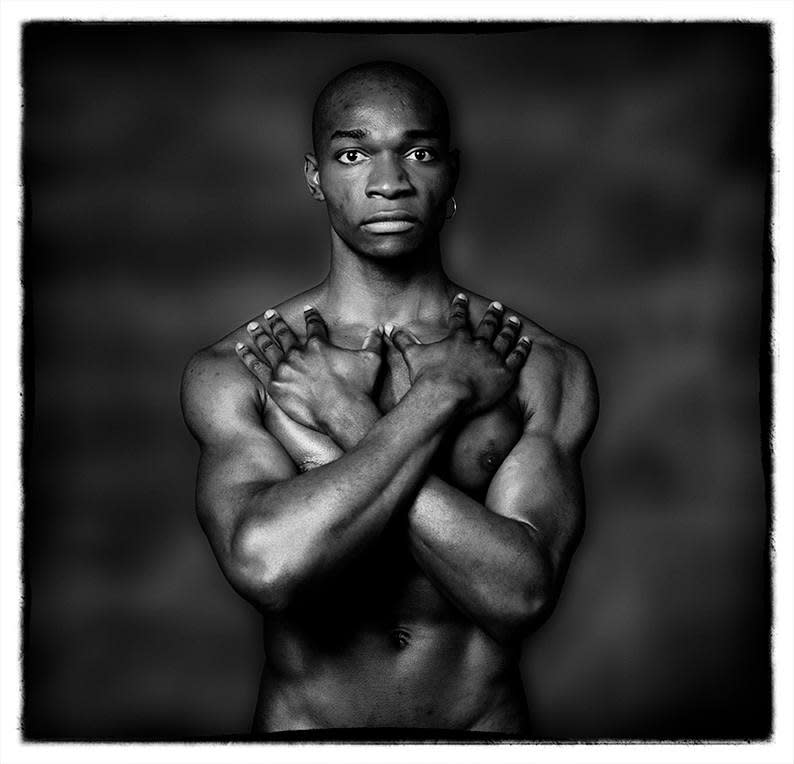

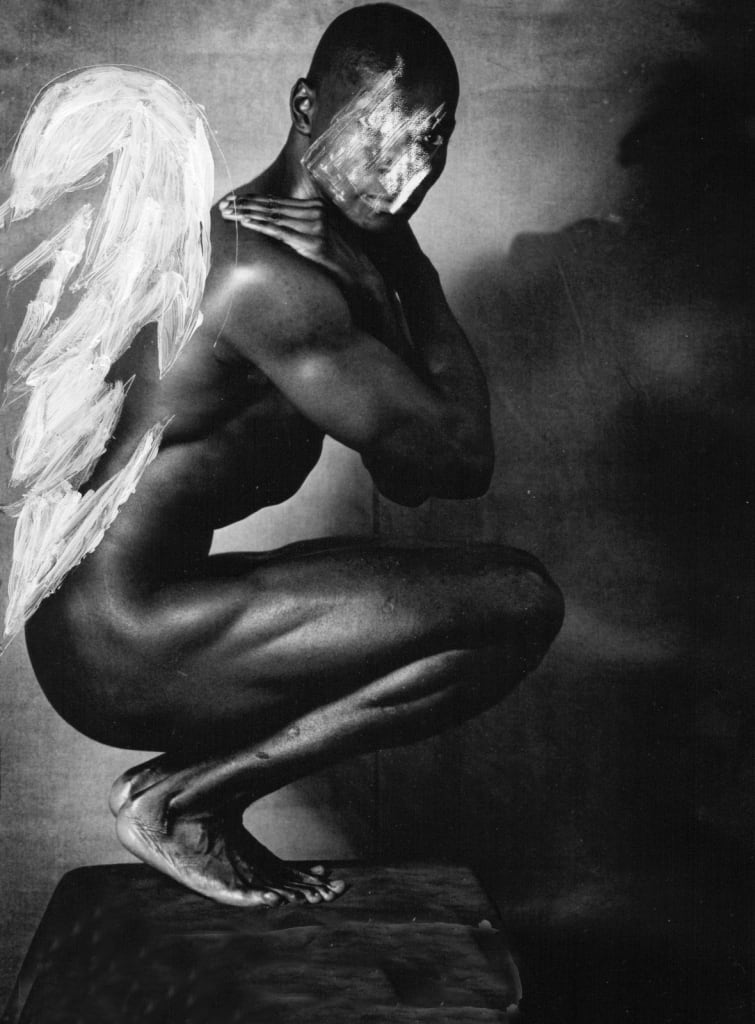

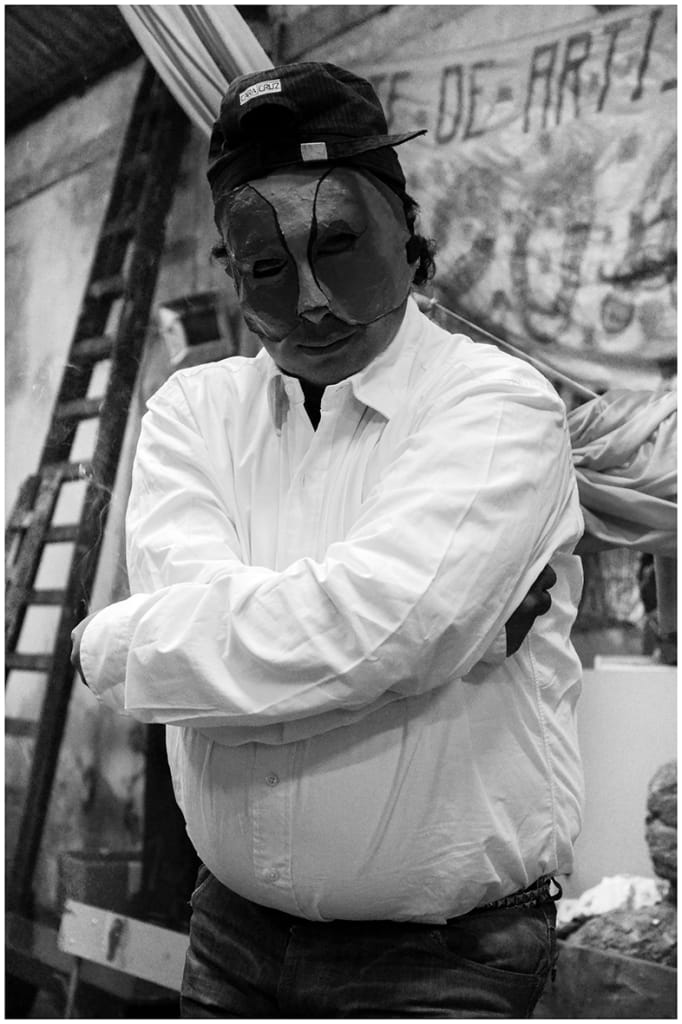

Being recognized by others is inseparable from the human condition. From its beginnings, philosophy has valued self-awareness and the search for true knowledge of oneself. Only through the recognition of others can a person constitute themselves as a distinct individual. Originally, the word “persona” meant “mask,” and through it, the individual acquired both a role and a social identity. The struggle for the mask was, in essence, the struggle for recognition.

Since the English colonial administration introduced the fingerprint classification system, the definition of a person has fundamentally changed. Identity shifted from being synonymous with “person,” a socially recognized subject, to being associated with biological data. In 1880, Bertillon developed the anthropometric-photographic system of personal identification, which soon became a standard for police forces and civil registries worldwide. With the rise of modern states, a person came to be defined by their nationality.

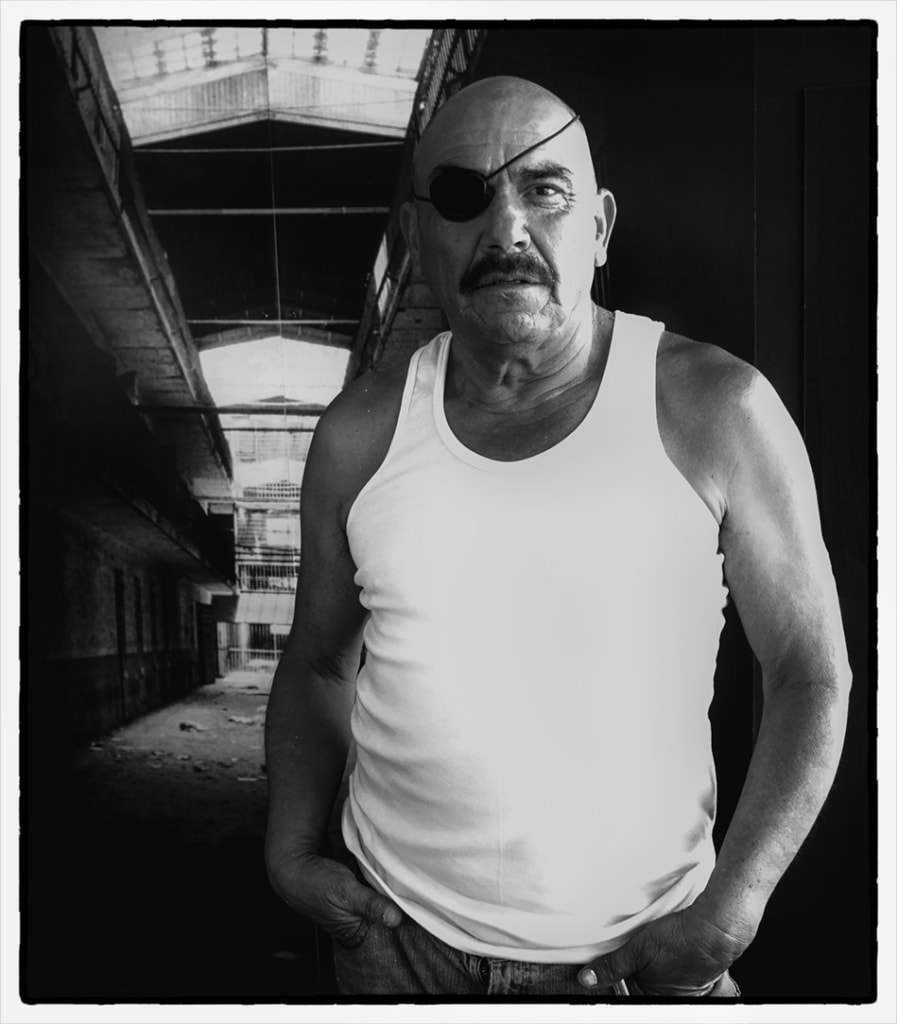

During the Nazi regime, deportees in concentration camps were not recognized by their names or nationalities, but by numbers engraved on their arms. Today, in contemporary societies, a person is identified by their DNA. In Europe, an international DNA registry of all its citizens is in preparation, conceived even before the Covid-19 pandemic. As Giorgio Agamben insightfully observes, a person is reduced to their “biometric” data, and identity is no longer synonymous with personhood. It is defined without reference to the person.

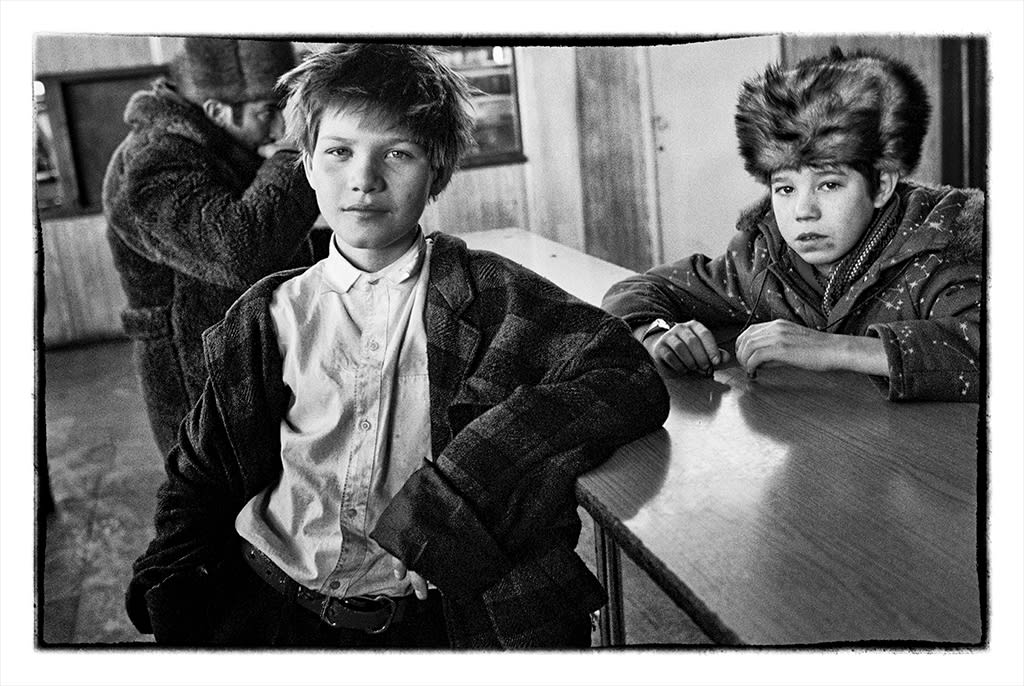

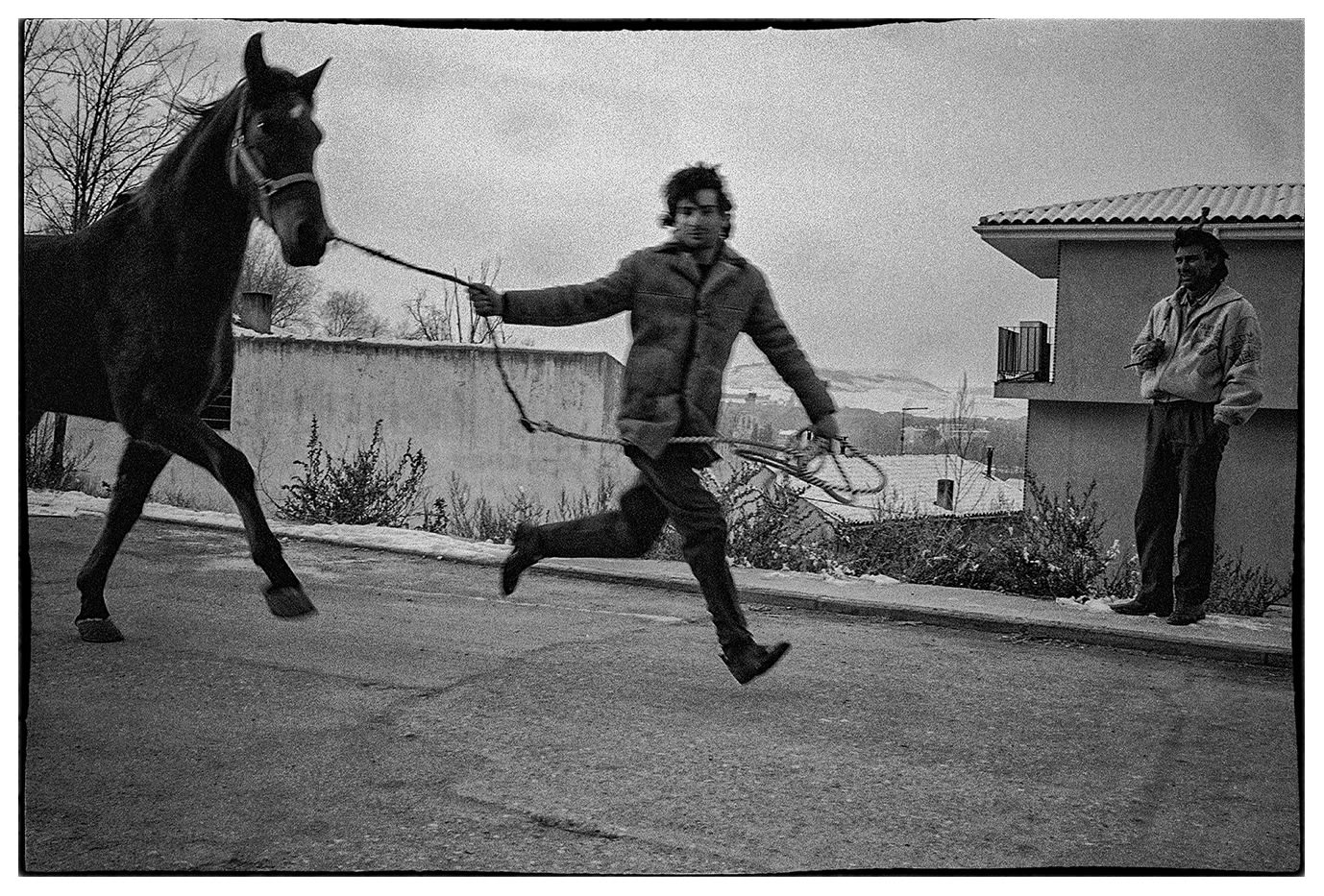

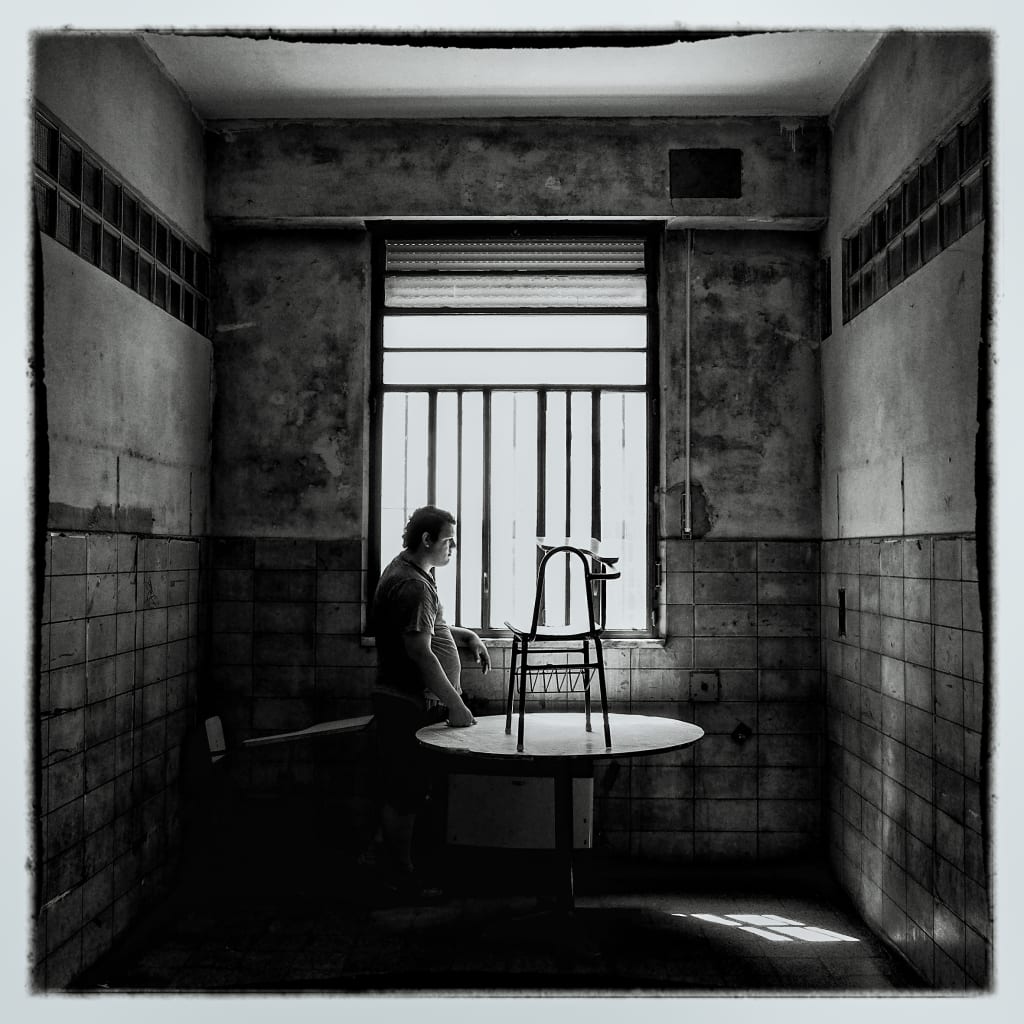

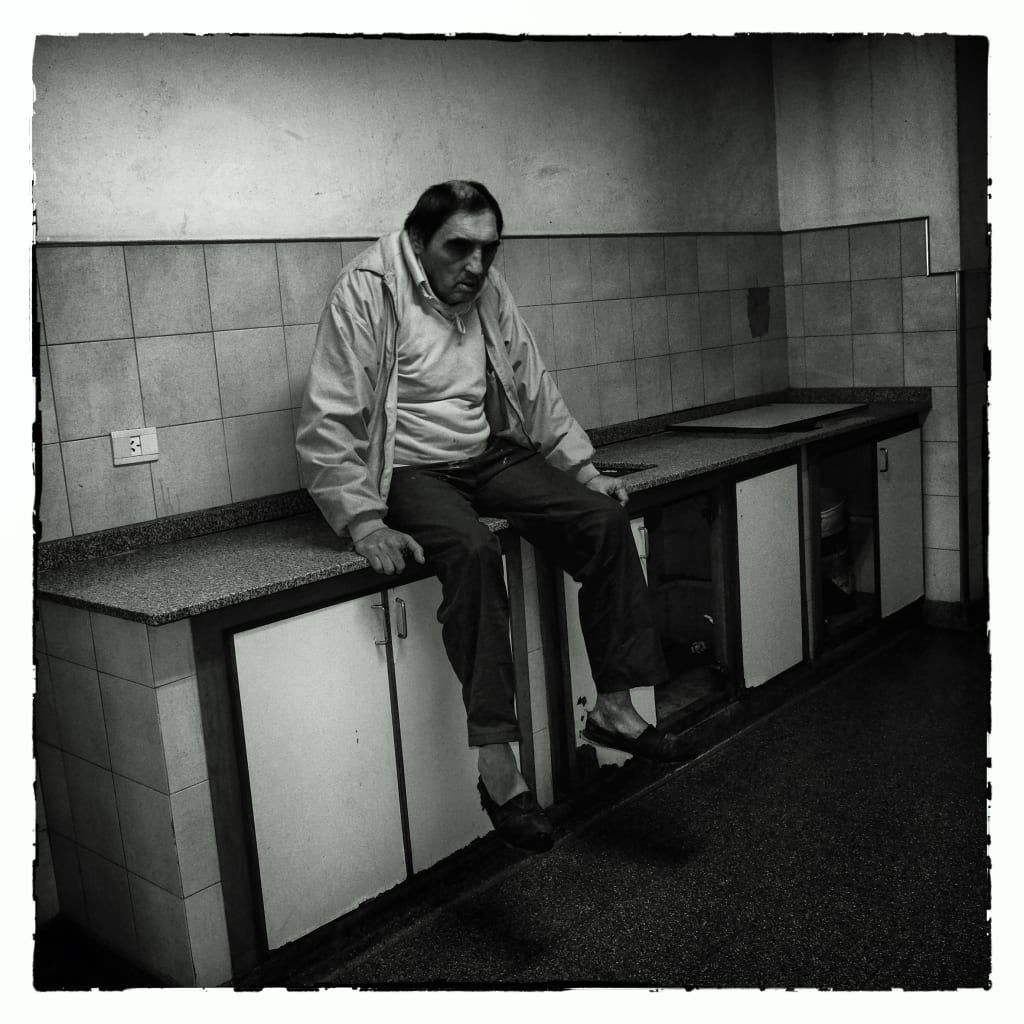

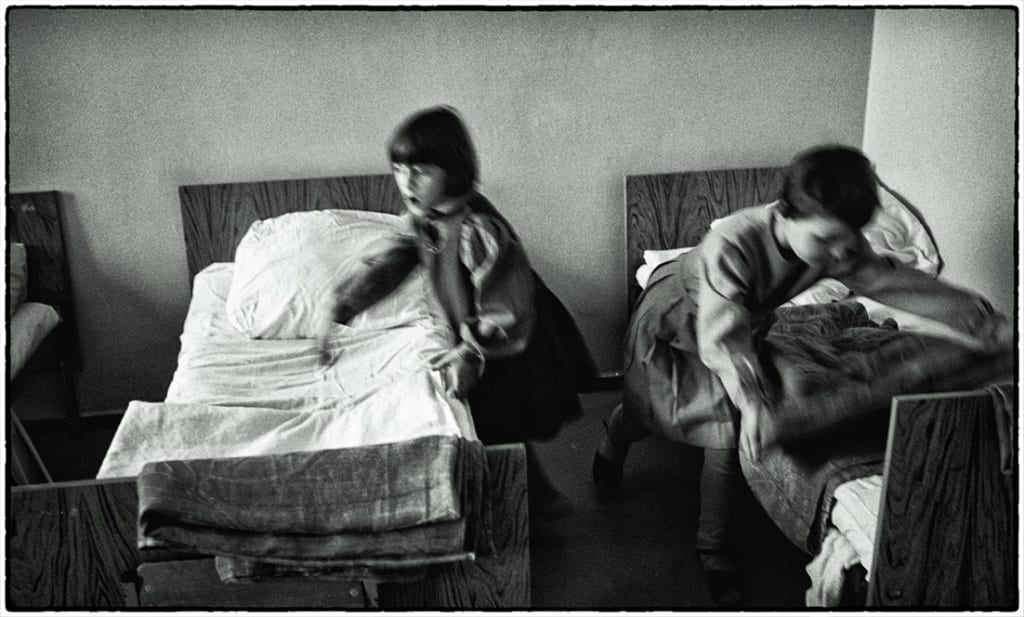

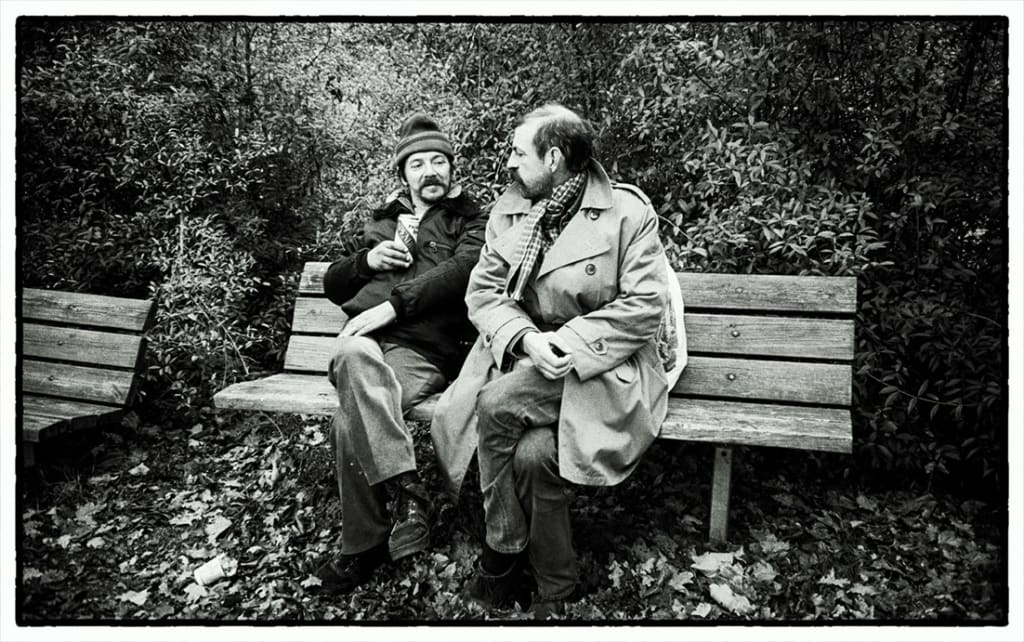

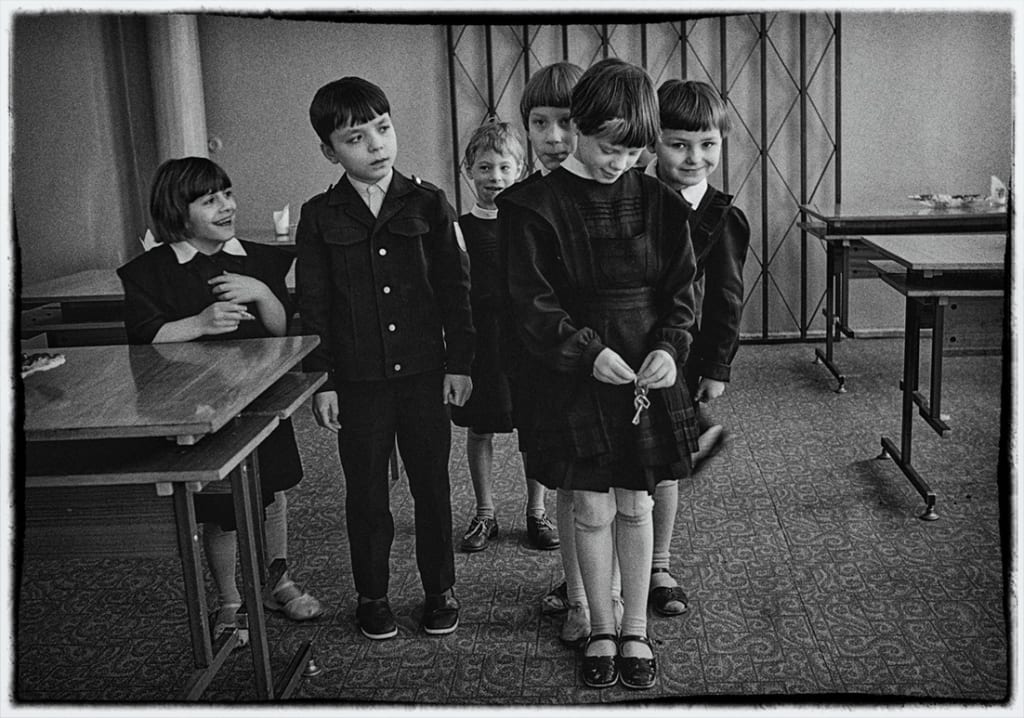

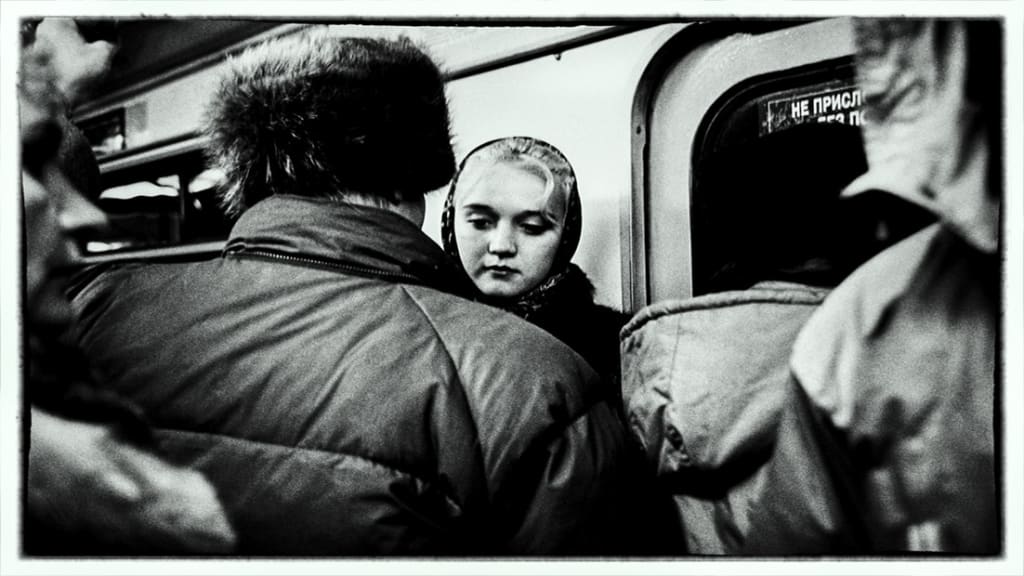

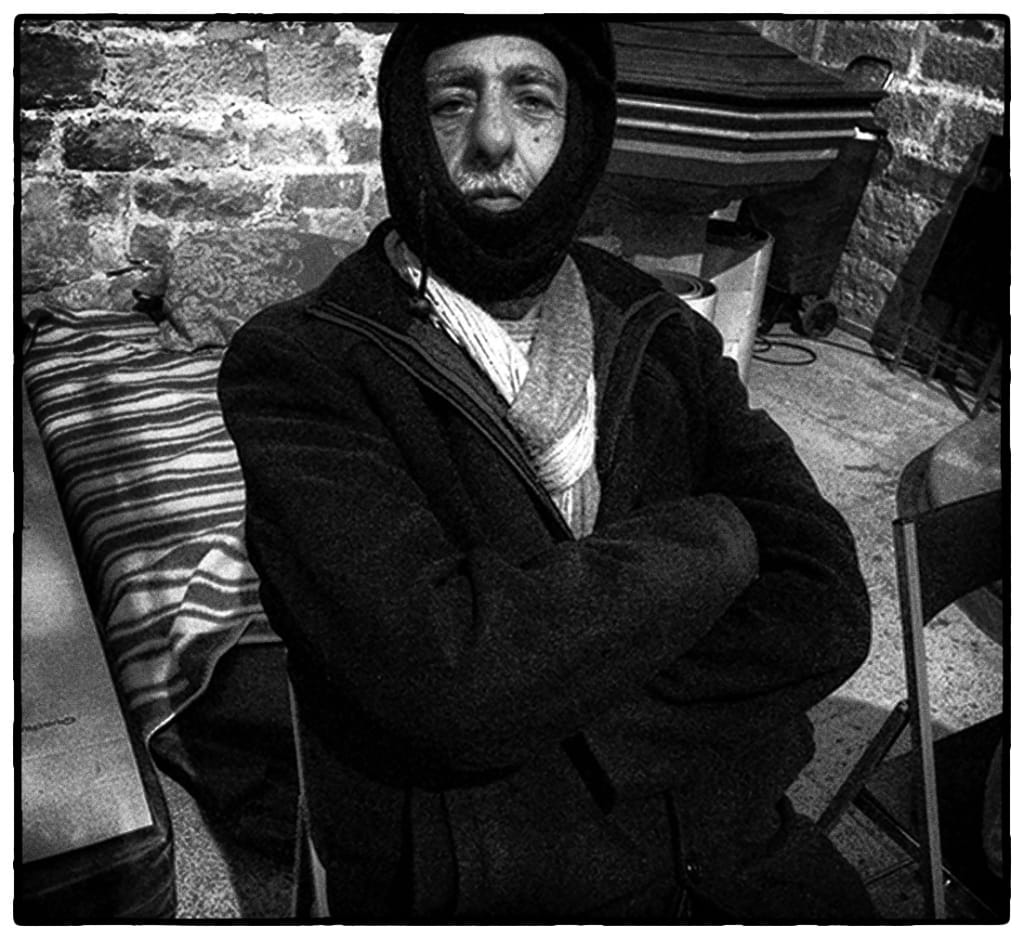

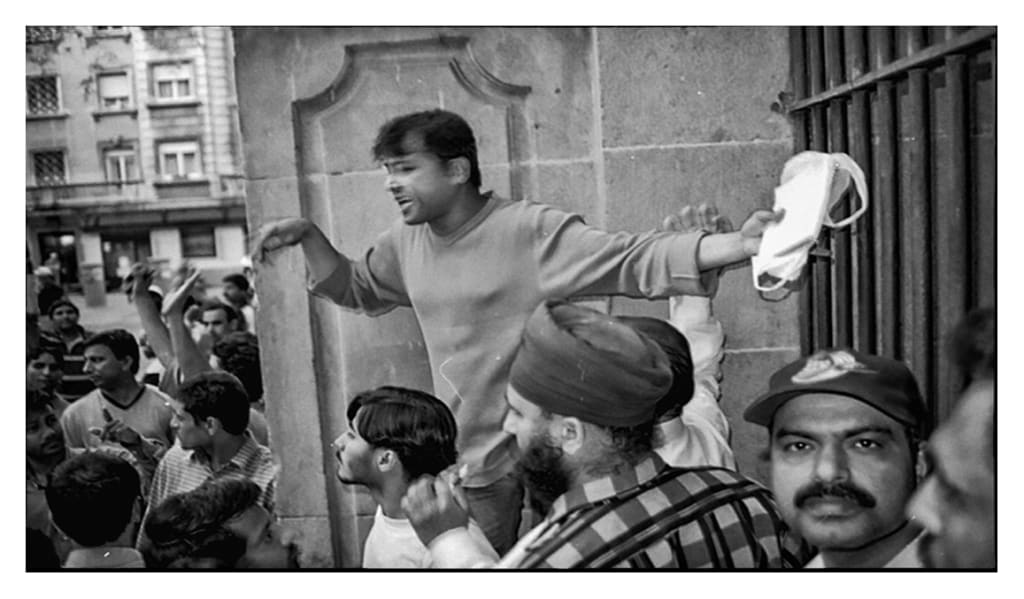

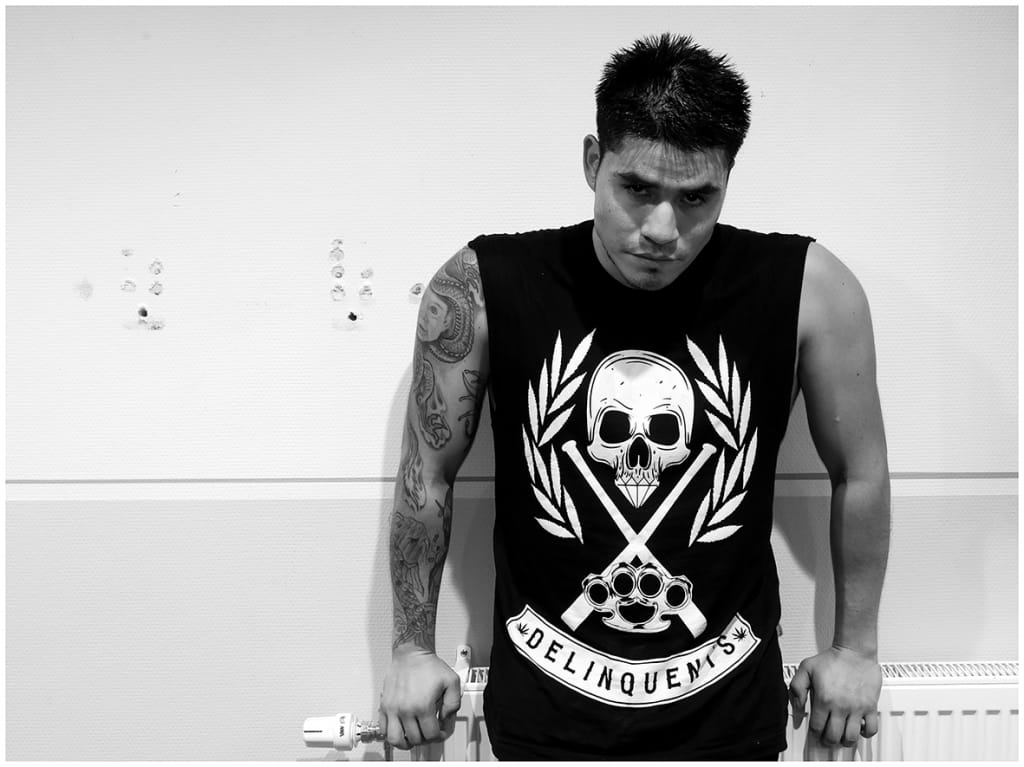

The struggle for social recognition has always been part of the human experience. In times of profound change, continuous crises, political instability, and an ever-growing number of refugees, people lose their traditional references: their country, their friends, their family, their language, and their roles in the society they once knew. In their attempt to create new spaces of recognition in the societies they enter, refugees and immigrants often encounter social exclusion. A constant feeling of humiliation invades them, reducing them to “the other,” viewed by the dominant classes as inferior or despicable, and at best, evoking only compassion or pity.

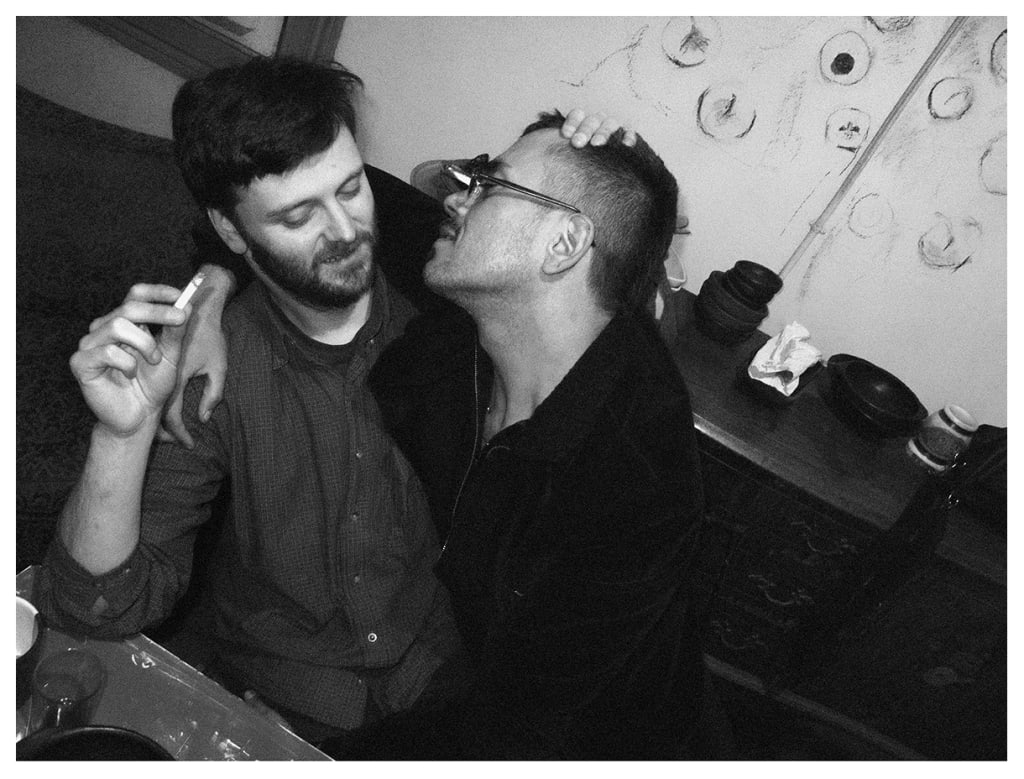

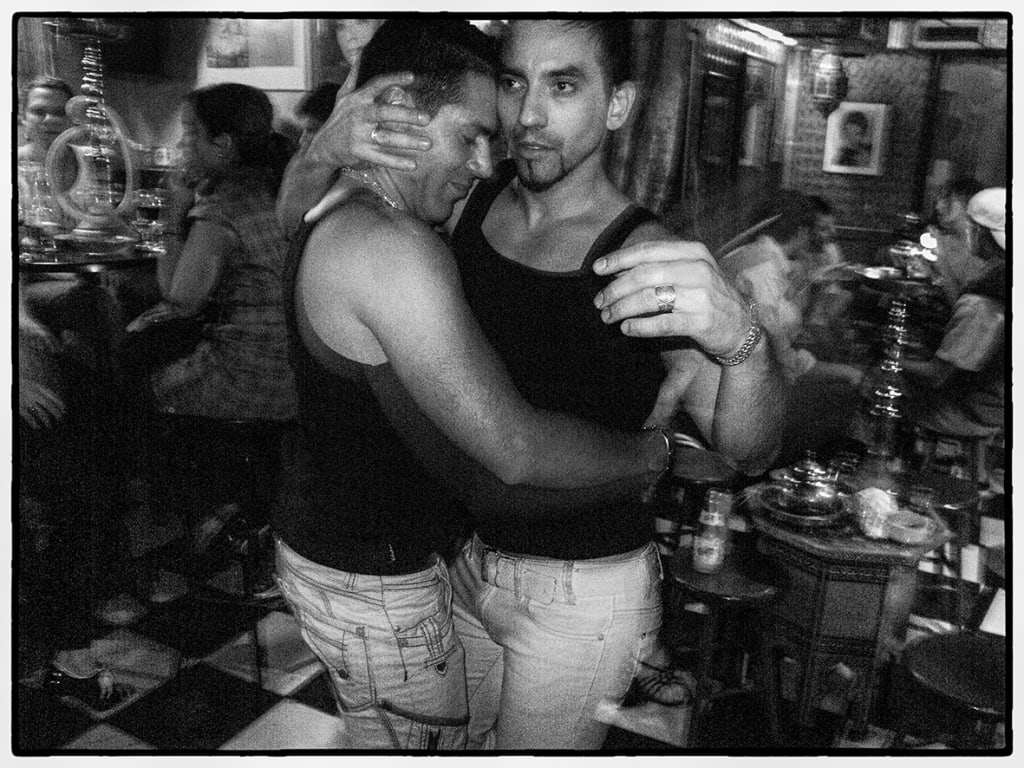

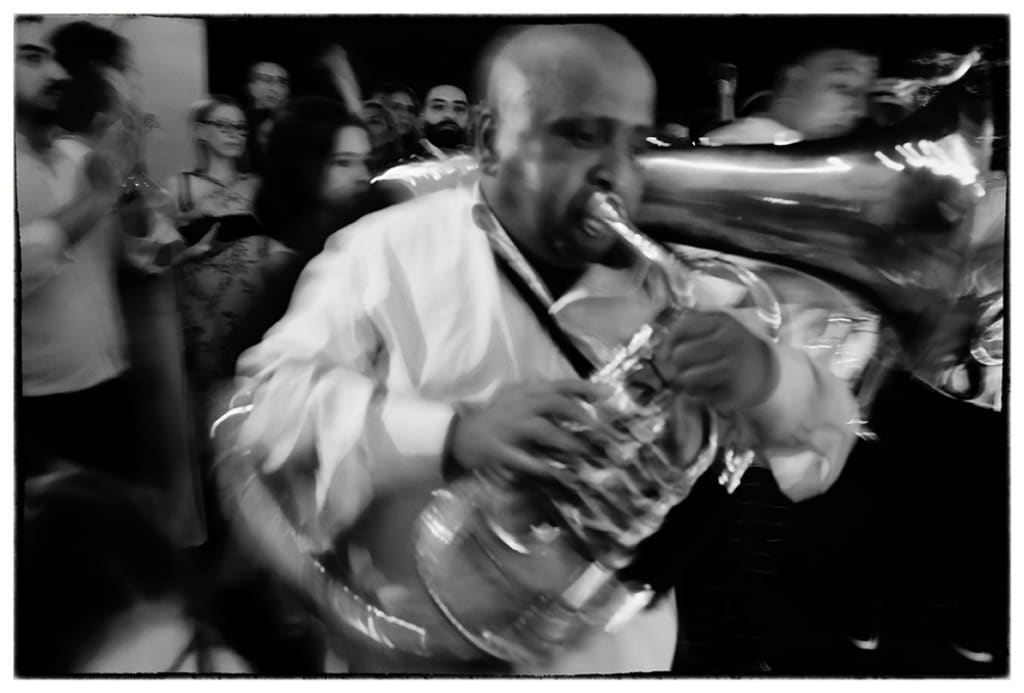

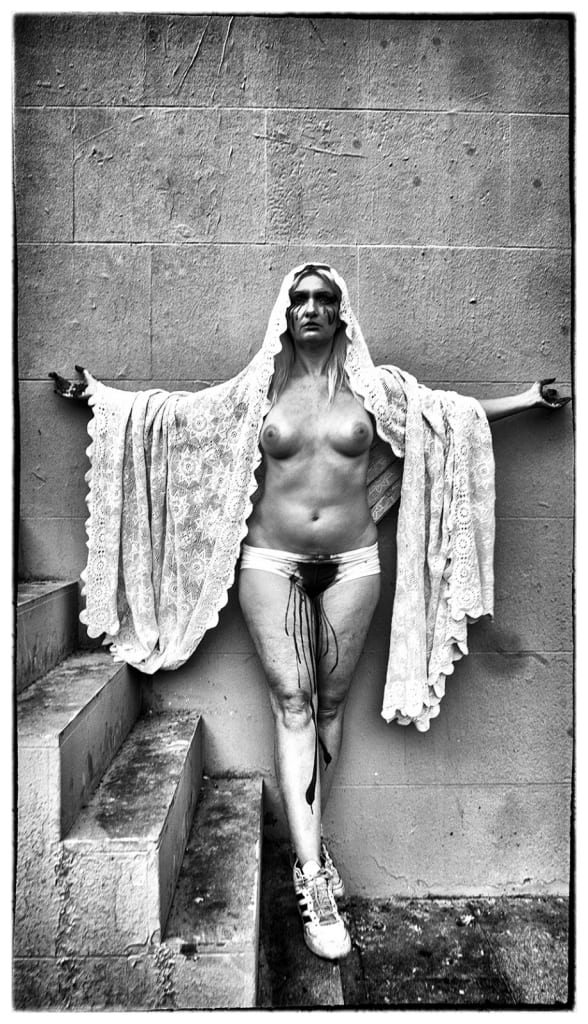

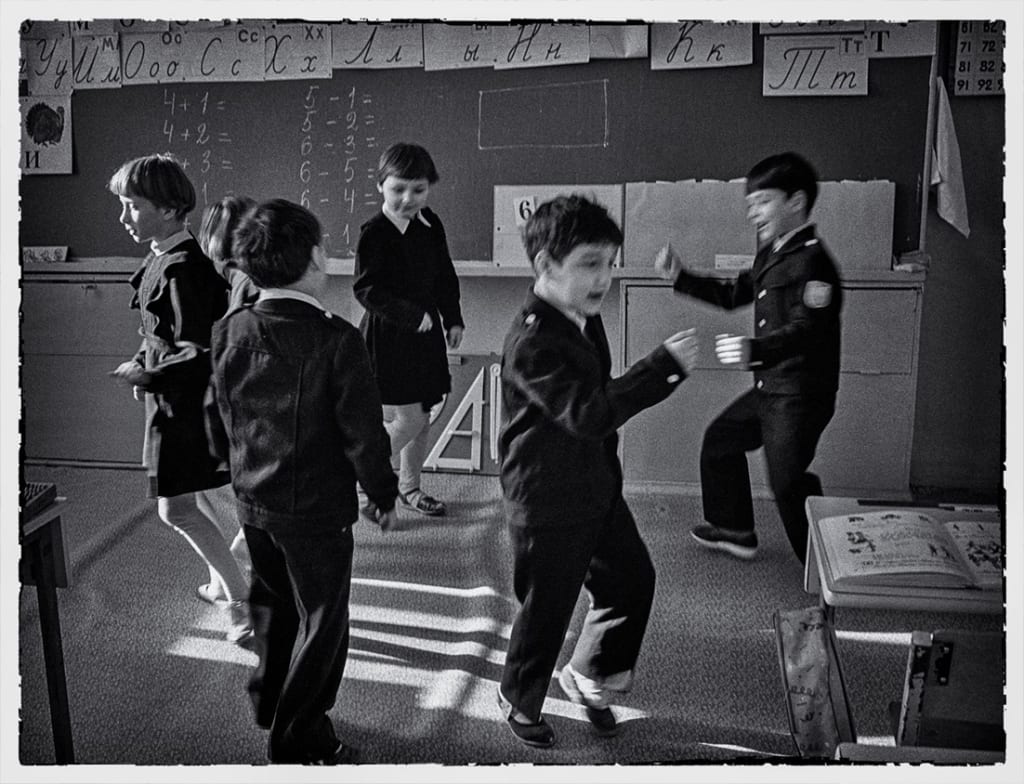

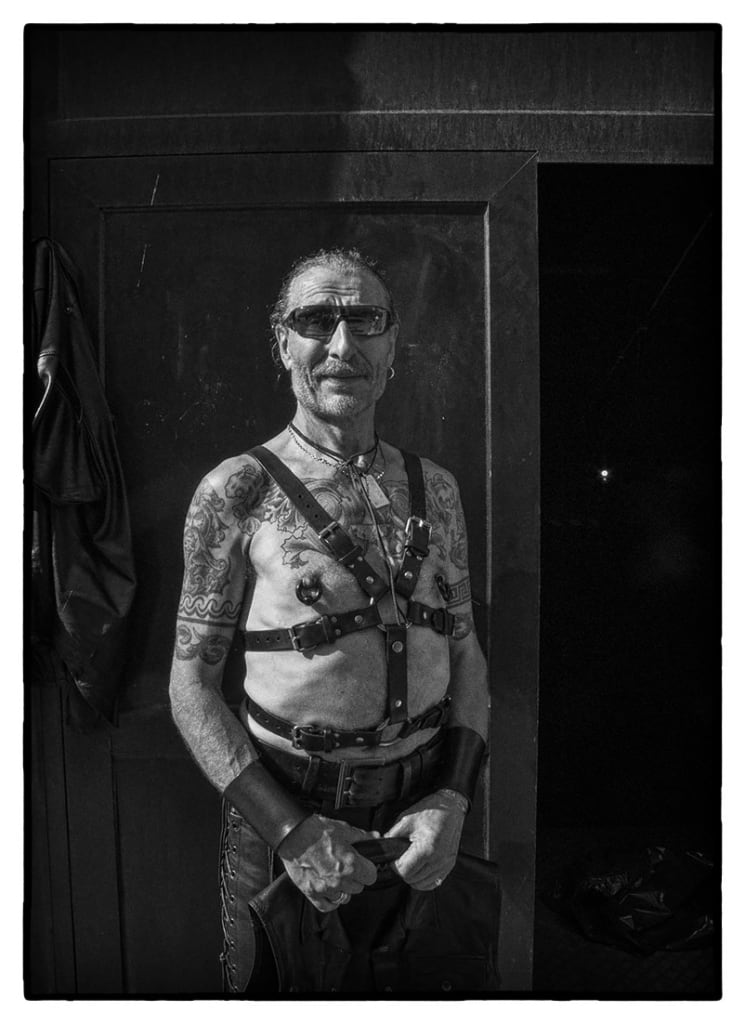

For a human being to emerge and fully express themselves, they must begin their process of becoming from a position, from a place. This is why I approach people with diverse histories who have lived in communities that are not their original ones but have made them their own—and yet, they continue to be treated as “the other.” In recent years, I have also encountered people of various sexual identities who, despite the well-meaning intentions of governments and states, continue to experience persistent exclusion.

It is easy for me to recognize “the other,” because I am one of them. It doesn’t matter where I have lived—whether in the suburbs of Stockholm, in the Chinese quarter of Barcelona, lost in villages in the Catalan countryside, in the old town of Panama City, or in the port district of Valparaíso—the question is always the same: Where are you from? It’s a question that has become part of my very being, a shadow that inevitably follows me wherever I go.

Patricio Salinas A