Portbou and the Belitres Pass

The path in the Pyrenees between Banyuls-sur-Mer and Portbou is, at times, unrecognizable. These are trails along steep slopes, difficult to traverse, especially in winter. Benjamin’s traces blend with those left by thousands of refugees, desperately fleeing war and death. The traces, like memory, are fragile: Benjamin knew that.

One of the mountain border crossings between France and Spain is called Coll de Belitres. In Catalan, “belitre” means undesirable, vile. The irony of history lies in the fact that Spanish refugees passed through there at the end of the Civil War in 1939. Later, in September 1940, Walter Benjamin would cross that same border, fleeing Nazi barbarism.

From my years of studying sociology, through my time in prison, and into my early years of exile, I was captivated by Benjamin’s texts: the city, the traces of history, the dialogue between barbarism and civilization, his works on Kafka, and his interest in the microcosmic. His writings offered me scattered and multifaceted images, yet deeply interconnected.

His Theses on the Philosophy of History, partially published two years after his death, is not a finished text: it’s a project. These are writings composed at different times, between late 1939 and early 1940, a collection of notes made in his notebook or on various scraps of paper, often in the margins of newspapers. In them, one finds the tiny handwriting of a man on the run, pursued by Nazi forces. Much speculation has arisen in an attempt to determine whether these notes were the ones Benjamin carried in his suitcase during his journey through the Pyrenees, just before committing suicide. No one knows for certain.

In Stockholm, I began to read about Benjamin’s life, his fate as an exile, his non-belonging, his escape to Paris, and his flight through the Pyrenees to Spain. Benjamin died in a border town, choosing suicide when he saw no other escape from persecution. He wanted to end the feeling of being a pariah, a homo sacer, as Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben would later call it.

Over the years, Benjamin’s last days and his flight through the Pyrenees became an obsession for me. What difficulties did he encounter during his passage through the mountains? What thoughts consumed him in his final hours? Which path did he take? The smugglers’ route? The Spanish refugees’? How did he arrive in Portbou? What did he find there? Did he speak to the locals? What are the true details of his death? Was he driven to suicide? Where did his documents and briefcase end up? His writings? His notebook? Were the Theses on the Philosophy of History inside that briefcase? Where did his body rest?

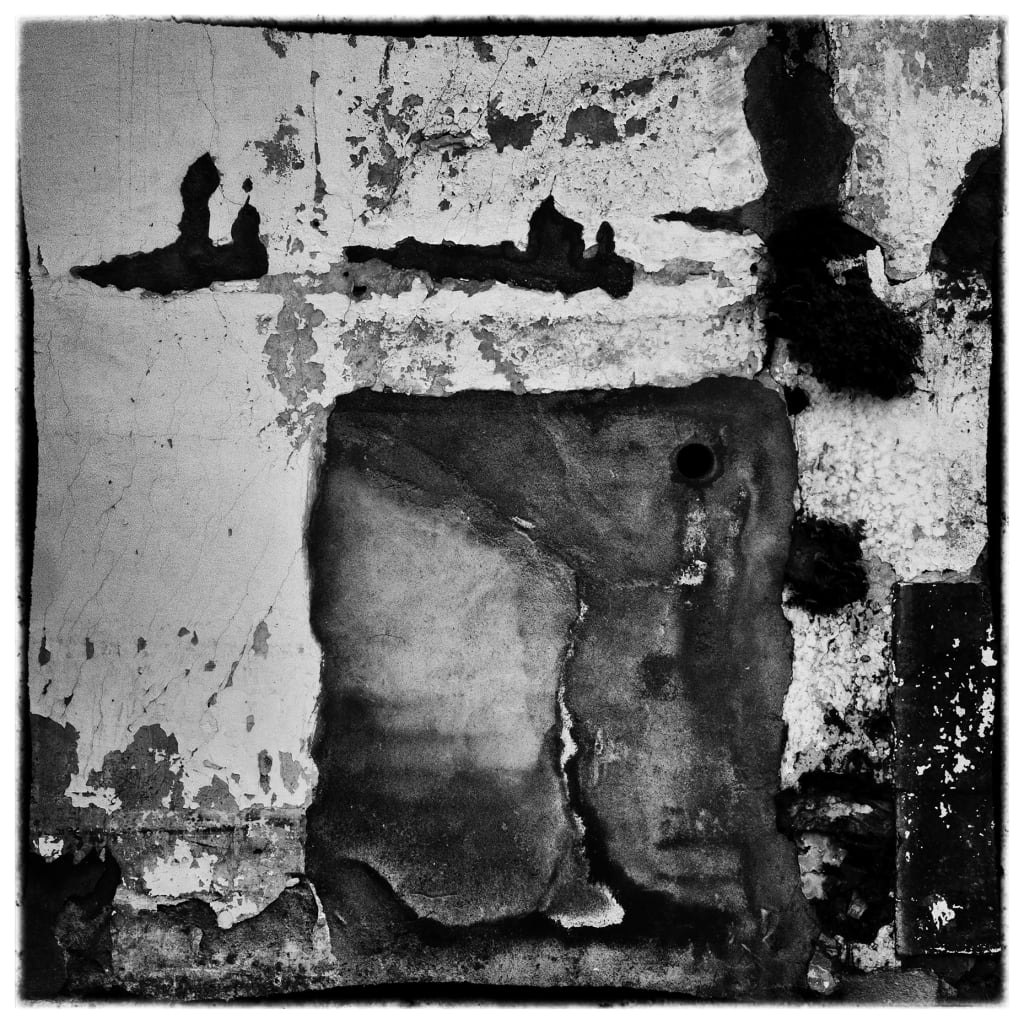

The path Benjamin followed was laden with the traces of other exiles fleeing the horrors of the Spanish Civil War or the Nazi invasion of France. The analogy between the trace and the path of history is clear. Benjamin understood that every historical journey leaves cultural traces—microcosms, which fascinated him. His constant observation of the minute, the traces of all past creation denoting the historicity of an object, was his deep preoccupation.

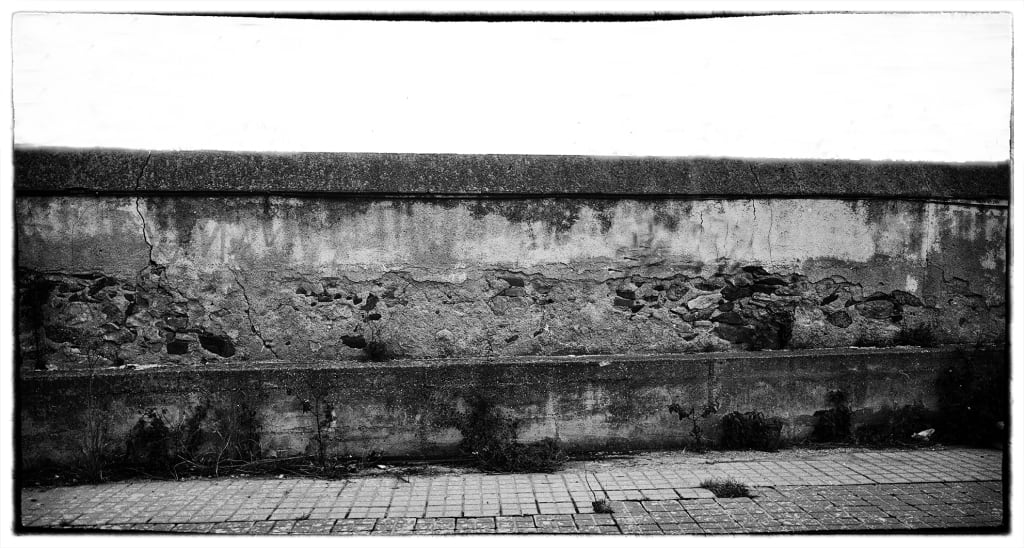

For three winter months in 2015 and three weeks in the spring of 2016, I dedicated myself to investigating the details of his journey. To do this, I lived in Banyuls-sur-Mer and Portbou, crossing the mountains several times on both sides of the border. It wasn’t always possible, as the hurricane-force tramontana winds sometimes made the route impassable. In Portbou, I found a desolate, decaying town, seemingly without a future. A place that lives off memories and past customs. The imposing railway station, which once served as a customs office and was a vital hub for goods and passengers crossing the border, is now in decline. If it weren’t for the occasional passenger traveling to Cerbère, in France, no one would even notice Portbou.

The cemetery where Benjamin’s remains are supposedly buried receives the occasional student, researcher, or lost tourist who stumbles upon Portbou by chance. Benjamin’s supposed grave looks out, solitary, toward the sea.

Patricio Salinas A, May 2016